Welcome to Noodles of Asia ! - A Woke Noodle Blog

Budae Jjigae: From Battlefield Scraps to a Simmering Symbol of Hope

Dive into the spicy, soulful history of Budae Jjigae, the Korean "army base stew" born from post-war scarcity, in our 1,500-word blog post at NoodlesOfAsia.com. Discover how this fusion of Spam, kimchi, and ramen became a symbol of hope for South Koreans and U.S. forces rebuilding after the Korean War. Includes a traditional recipe and an Americanized version to savor this tale of resilience. #BudaeJjigae #NoodlesForJustice

Woke Noodles - NoodlesofAsia.com

8/11/20256 min read

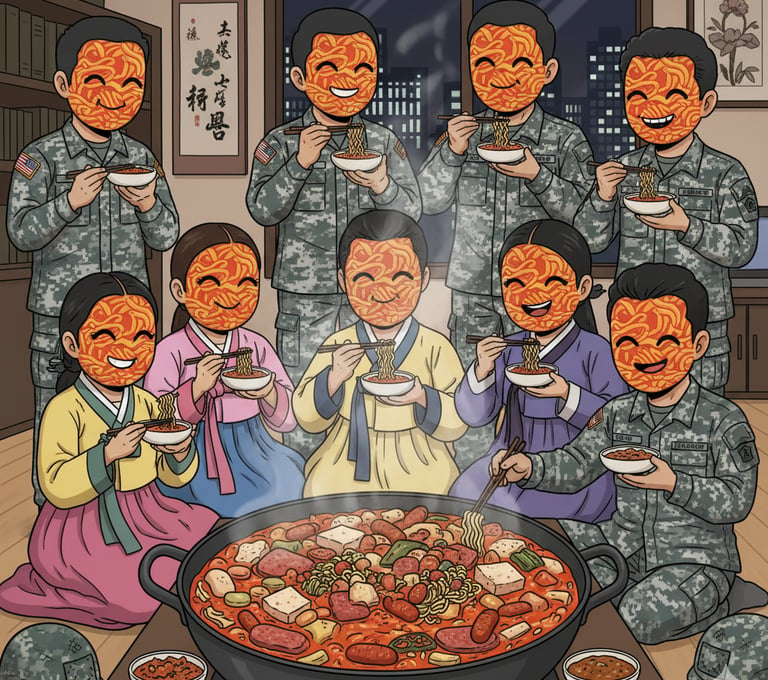

In the heart of South Korea's bustling street food scene, amid the sizzle of grilling meats and the steam rising from communal hot pots, one dish stands out as a testament to resilience and reinvention: Budae Jjigae, or "army base stew." This fiery, communal pot of bubbling broth, loaded with kimchi, Spam, sausages, ramen noodles, and an eclectic mix of ingredients, isn't just comfort food—it's a flavorful chronicle of survival. Born from the ashes of the Korean War, Budae Jjigae emerged as a fusion of desperation and ingenuity, blending Korean staples with surplus American military rations. For South Koreans rebuilding a shattered nation and American forces stationed in the DMZ's shadow, this stew became more than sustenance; it was a beacon of hope, a shared meal that whispered promises of rejuvenation amid the rubble. In this 1,500-word journey, we'll trace its gritty origins, unpack its profound symbolism, and even guide you through preparing both a traditional version and an Americanized twist—because some histories are best savored one spicy spoonful at a time.

The Birth of a Stew: Origins in Post-War Scarcity

The Korean War (1950-1953) left the peninsula in ruins. Over three million lives lost, cities reduced to smoldering craters, and a population teetering on the brink of famine. South Korea, divided from the North and occupied by U.S. forces, faced acute food shortages. Rice fields lay fallow, livestock decimated, and traditional ingredients like pork or beef were luxuries few could afford. It was in this crucible of hardship, near U.S. military bases in cities like Uijeongbu and Pyeongtaek, that Budae Jjigae was born.

The dish's name tells its story: "Budae" translates to "military unit" or "army base," while "jjigae" simply means "stew." In the war's immediate aftermath, enterprising locals—often base workers or black-market traders—scavenged leftovers from American mess halls. Canned goods like Spam, Vienna sausages, bacon, and baked beans, intended for GIs but discarded as waste, became prized commodities. These processed imports, shelf-stable and calorie-dense, were bartered or smuggled in exchange for Korean vegetables and ferments like kimchi.

Early iterations were humble, almost clandestine. One precursor, known as "kkulkkuri-juk" or "piggy porridge," was a rudimentary mash of scavenged meats simmered in a thin broth—more survival gruel than gourmet fare. By the late 1950s, as U.S. troops settled into permanent bases under the Mutual Defense Treaty, the stew evolved. Koreans near Camp Casey or Osan Air Base would pool resources: fiery gochujang paste for heat, anchovy stock for depth, and instant ramen noodles (introduced via American aid) for heartiness. The result? A one-pot wonder that stretched meager rations to feed families or impromptu gatherings.

This wasn't always celebrated. In the 1970s, under President Park Chung-hee's authoritarian regime, Budae Jjigae faced a ban. The government, pushing for self-reliance and wary of "Western corruption," outlawed the use of imported canned goods, viewing the dish as a symbol of dependency. Underground eateries persisted, however, simmering pots in defiance. By the 1980s, as South Korea's "Miracle on the Han River" economy boomed, the stew shed its stigma. Restaurants proliferated, and nicknames like "Johnson Tang" (after President Lyndon B. Johnson, who visited in 1966) or "Yankee Stew" faded into affectionate folklore.

Today, Budae Jjigae is ubiquitous—from hole-in-the-wall spots in Seoul's Itaewon district to high-end fusions in Los Angeles Koreatowns. Its journey from black-market necessity to national treasure mirrors South Korea's own arc: from war-torn poverty to global powerhouse.

A Pot of Hope: Rejuvenation for Koreans and Americans Alike

Beyond its ingredients, Budae Jjigae carries the weight of collective memory. For South Koreans, it embodies the unyielding spirit of reconstruction. In the 1950s, with GDP per capita hovering below $100 and orphans wandering bombed-out streets, every meal was a small victory. This stew, cobbled from "enemy" scraps—yet transformed with kimchi's tang and gochugaru's blaze—represented alchemy. It turned humiliation into empowerment, scarcity into abundance.

Imagine a family in Uijeongbu, 1955: Father, a former conscript, trades labor at the base for a can of Spam. Mother ferments cabbage scraps into kimchi. Together, over a butane stove, they create a bubbling cauldron that fills the air with savory promise. For children scarred by air raids, the first slurp—salty, spicy, chewy with noodles—tasted like normalcy returning. It was hope in edible form: a reminder that even in division's shadow, communities could rebuild, innovate, and share.

For American forces, the dish fostered unexpected bonds. U.S. soldiers, far from home amid tense Cold War standoffs, found solace in these hybrid meals. Base-adjacent restaurants became cultural crossroads, where GIs swapped stories with locals over steaming pots. "It was our way of saying, 'We're in this together,'" recalls a veteran in a 2017 Army article. The stew symbolized alliance—not just military, but human. Spam, once derided as "mystery meat," became a bridge, evoking stateside barbecues while embracing Korean heat. In a region still technically at war (the armistice of 1953 endures, not peace), Budae Jjigae offered rejuvenation: a pause from patrols, a taste of fusion that hinted at lasting partnership.

This duality persists. During the 1990s IMF crisis, when Korea again faced economic peril, Budae Jjigae joints surged as affordable comfort. And in 2020, amid COVID lockdowns, its one-pot communal style evoked wartime solidarity anew. Sociologists like those at the Korea Policy Institute see it as a "delicious reminder" of resilience: a dish that honors the past while fueling the future. In an era of global tensions, it whispers that shared tables can heal divides—much like instant noodles unite activists worldwide in calls for justice.

Crafting the Classic: A Traditional Budae Jjigae Recipe

Ready to channel that history? This traditional recipe serves 4-6, evoking the post-war pots simmered near U.S. bases. Prep time: 20 minutes. Cook time: 30 minutes.

Ingredients:

Broth Base:

8 cups anchovy or kelp stock (dashima broth; substitute chicken stock if needed)

3 Tbsp gochujang (Korean red chili paste)

2 Tbsp gochugaru (Korean chili flakes)

2 Tbsp soy sauce

1 Tbsp doenjang (fermented soybean paste)

1 tsp sugar

4 garlic cloves, minced

1-inch ginger, grated

Proteins and Veggies:

1/2 block firm tofu, sliced

1/2 can Spam, cubed

2 hot dogs or beef sausages, sliced

1 cup kimchi, chopped (with juices)

1/2 cup tteok (rice cakes), soaked

8 oz enoki mushrooms, trimmed

1 small zucchini, sliced

2 green onions, chopped

1/2 onion, sliced

1/2 cup baked beans (canned)

Noodles and Finish:

2 packs instant ramen noodles (discard seasoning)

Optional: Sliced American cheese for melting on top

Instructions:

Make the Sauce: In a bowl, whisk gochujang, gochugaru, soy sauce, doenjang, sugar, garlic, and ginger into a paste. Set aside.

Prep the Pot: In a large, shallow pot or electric skillet (ttukbaegi-style), layer the base: Arrange kimchi, Spam, sausages, tofu, rice cakes, mushrooms, zucchini, onion, and baked beans in sections for visual appeal.

Add Broth: Pour stock over the ingredients. Dollop the chili paste mixture in the center. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat, then simmer for 10-15 minutes, allowing flavors to meld. The broth should turn a vibrant red, spicy and savory.

Incorporate Noodles: Nestle ramen noodles into the pot, pushing them under the broth. Cook 3-5 minutes until al dente. Stir gently to combine.

Serve Communally: Ladle into bowls or eat straight from the pot. Top with green onions and cheese if desired—it melts into gooey pools. Pair with rice and banchan (side dishes) like kkakdugi (cubed radish kimchi).

This version stays true to its roots: bold, unapologetic, and born of necessity.

An American Twist: Stateside Spam Symphony

For those Stateside, where Spam is a Hawaiian staple and Korean markets abound, here's an adapted version that's easier on the spice and wallet. It nods to GI nostalgia with cheddar and corn, serving 4. Prep: 15 minutes. Cook: 25 minutes.

Ingredients:

Broth Base:

6 cups low-sodium beef or chicken broth

2 Tbsp gochujang (reduce to 1 for milder heat)

1 Tbsp gochugaru

2 Tbsp hoisin sauce (for subtle sweetness)

1 Tbsp fish sauce

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 tsp sesame oil

Proteins and Veggies:

1 can Spam, diced

4 slices bacon, chopped

1 cup sauerkraut (sub for kimchi if unavailable)

1 cup frozen corn kernels

1 bell pepper, sliced

8 oz button mushrooms, quartered

1 carrot, julienned

1/2 cup canned kidney beans, drained

Noodles and Finish:

2 packs ramen noodles

4 slices cheddar cheese

Chopped scallions and cilantro for garnish

Instructions:

Sauce It Up: Mix gochujang, gochugaru, hoisin, fish sauce, garlic, and sesame oil.

Build the Layers: In a Dutch oven, scatter bacon and Spam. Add sauerkraut, corn, bell pepper, mushrooms, carrot, and beans.

Simmer Away: Pour in broth, add sauce. Boil, then reduce to simmer for 10 minutes. The corn adds pops of sweetness, evoking Midwest comfort.

Noodle Dive: Add ramen; cook 3 minutes. Top with cheese slices to melt.

Dig In: Garnish with scallions and cilantro. Serve with Texas toast for dipping—pure fusion flair.

This tweak makes it backyard-barbecue friendly, bridging Korean grit with American heartiness.

From Stew to Legacy: A Lasting Simmer

Budae Jjigae isn't frozen in 1953's trenches; it's evolving. In K-dramas like Crash Landing on You, it pops up as nostalgic fare. Globally, chefs like David Chang riff on it with truffles or vegan swaps. Yet its core endures: a reminder that from war's detritus, hope can bubble forth.

For South Koreans, it honors the 1.5 million civilian dead, the partitioned families, and the economic phoenix that rose. For Americans, it's a quiet nod to 28,000 troops still guarding the 38th parallel—a shared legacy of alliance forged in flavor. In our divided world, perhaps we all need a pot like this: spicy enough to wake us, communal enough to unite us.

Next time you cradle a bowl, think of Uijeongbu's flickering lanterns, the laughter over contraband cans. Budae Jjigae isn't just stew—it's revival, one ladle at a time. What's your fusion story? Share in the comments.